We get called for an OD. A young woman took all her psych meds at the same time because she was depressed. Her ex-boyfriend broke into her house and stole her cell phone. And her best female friend committed suicide recently, so she was just feeling a little overwhelmed. She had a past history of suicide attempts, but she said she wasn't try to hurt herself this time -- she just wanted to chill out. Sitting in a chair in the kitchen she was slurring her speech, and when she tried to stand, her balance was poor. At first I thought she was in her late thirties. I found out she was just thirty.

We got her out in the ambulance and she lay down on the stretcher, and despite the wear and tear on her face, I could see she was actually a fairly pretty girl. It didn't hurt that she was wearing a tank top that showed off a decent body -- one that she said she used to spend a lot of time in the gymn toning -- lifting weights, doing cardio. She had a flat abdomen with a navel ring, and a chest that certainly would have had the guys in the gymn checking her out when she walked past. She had beautiful long hair.

I told her I had to do an IV and when I looked at her arms, I could see track marks. "Good luck," she said. "My veins suck. When I used to work out they were bulging ropes. Not any more."

"Where do they sometimes find a vein?" I asked.

"Between my toes."

No, she didn't actually say that. She said, as she turned her wrist at a peculiar angle, and then with her mouth, kissed the inside aspect, "Right about here, if you wap it a couple times, a little one might pop up."

I couldn't find anything there. Instead I found a vein I could put a 24 in in her forearm. It was hidden from view, but I could feel it beneath the surface with my finger tips. I sunk it and filled four blood tubes.

"You're good," she said.

I was impressed with myself. I was thinking maybe she'll invite me to shoot her and her pals up at their next house party. But...

When we were talking about working out and why she hadn't been in the gymn, she said she stopped going after she got burned. She'd had to go to rehab instead. She told me how her ex-roommate -- a woman she'd met in N.A. -- a woman who she said was "kind of paranoid" -- had poured boiling water on her one night when she was sleeping, and said, "You're not so pretty now, are you dearie?" For a couple years after that she could barely lift her arm above her shoulder, although it was better now.

Not the kind of friends I would want to hang around with. It was amazing she wasn't scared more badly. You could see the burns on her neck, but her face with the help of grafts and a damn good surgeon, made her look okay considering.

Hard life.

This paramedic blog contains notes from my journal. Some of the characters, details, dates and settings have been changed to protect the confidentiality of people and patients involved.

Sunday, November 27, 2005

Thursday, November 24, 2005

Thanksgiving

It’s Thanksgiving morning. I awake at 5:10, shower and dress, then open up the garage door to see a couple inches of snow on the ground. It’s beautiful, but I hate winter, hate the cold weather, hate driving in snow.

When I get to the base, I can see from the tracks in the snow by the ambulance doors. The night crew is out on a call. Ten minutes later I hear them clear with a presumption. I sit in the office and drink a diet coke while I read the morning paper.

This week a thirty-year-old female cop in one of the suburban towns was murdered by her ex-boyfriend, a state cop. We had two cars on standby while they looked for the shooter. They found him a couple hours later, also dead. The paper said he parked his car at a park, and then walked over to her house so she wouldn’t see him. He lay in wait for her and when she returned from work, he ambushed her, shooting her three times, twice in the chest and once in the head. He was supposed to turn himself into court today on a police charge, but instead he called his lawyer and said there was a change in plans. The lawyer got the message a couple hours later and alerted police. Her new boyfriend -- another cop -- came home and found her.

I knew her by face, not by name. I’d been on calls with her a few times over the six years. I remember when she first started working. She was gorgeous. It was hard to believe someone that good-looking would chose to be a cop. Lately I noticed she’d started to wear a bit more makeup around her eyes, her face seemed a little heavier. She never had much to say to us, at least on the calls I went on. She was all business. If she pulled you over, I don't think you'd want to sweet talk her. I’m sure she had a warm side she showed to those who knew her.

The paper in the news rack the next day had a headline “A Cop’s Fury.” It had pictures of the two dead on the front. It made me think, you are here one day, and the next people are walking by the news rack with your picture on it, only you aren’t one of the people walking by to see it.

**

We did a call in her town this morning, and said our condolences to the two cops who were there. They had black bands over their badges. The call was for an old woman who said she had taken a handful of painkillers. She said she did it because she was stupid. She said her ex-husband and her doctor would be mad. I got the feeling from the cops they were at this house all the time for similar vague complaints of taking too many pills. “I don’t need this today,” one cop said to me.

**

All week I have found myself in idle moments thinking about the dead policewoman. I guess she probably never figured her death was coming that day. She comes home from work, sits down with computer and then suddenly there is the angry man in her house, gun drawn coming at it. Did she know she was going to die?

When do heart attack victims get that sense that right now what is happening -- this sudden pain in their chest -- might be their end? And car crash victims – they start to loose control and see the tree or the truck careening toward them?

Last New Year’s Eve another cop in the same department was gunned down at a domestic. I knew him too, but also just in passing. We’d been on calls together. A nice, big friendly man. He walked down the basement stairs and then shooter pulled the trigger on a machine gun. Did he have time to realize his end had come?

This summer a paramedic student who rode with me was on a jet ski with his girl friend in Florida when they were blindsided by a boat. I heard about it when I saw his obituary posted at the office. Did he hear the roar of the engine? Did he turn to see it bearing down on him? What did he think in those moments?

Last Saturday they held a memorial for a flight nurse who died in a helicopter crash 13 years ago. I was working in the health department at the time and remember the late night call I got telling me about the crash. I’d seen her around the ER a few times when I brought in patients as a volunteer EMT. And I had ridden in the helicopter as a third rider only a month before. The accident happened when the copter clipped a wire while trying to land near a highway rest stop, a rest stop that now bears her name. When the copter started spinning, did she know?

I don’t mean to be morbid.

The saddest thing about all these deaths is not just the fear they must have felt when they saw what was happening to them, but that fact that everything that would have happened in their lives and all the people they would have affected is just gone. The children the might have had, the things those children would have gone on to do, the memories – all of it vanished. That’s the tragedy.

Death happens everyday and we see it in this job, but it doesn’t impact as much unless it is one of us. You can grow immune to it until it comes close like it has again this week.

But I don’t worry as much about dying as I used to. I’ve lived awhile now and feel lucky to have made it as long as I have. If the deal was when I was born, I agreed to come out of the womb, but in return I would only have these 47 years, I'd take that deal anytime.

I have many, many years ahead I hope. But if I were to die today, if the door were to open and death were to be there, I would be terrified, but I can’t say that I would have been cheated. Life, with its share of sadness and disappointments, has been largely good to me. And today I am as excited about life and its possibilities as I ever have been, excited not in the wild way I was as a youth, but in the more realistic sense that I can enjoy the moments now and not just the thought of the goal.

I want to live fully and feel, for the most part, I have been. I work a lot, but I like my job and the money I make will help me keep doing what I love – being a paramedic, writing, going to foreign countries to help the poor, getting good seats to a Red Sox game every year, living in my house which I feel comfortable in, being able to eat a good steak, and drink a cold beer when I want without having to count nickels on the liquor store counter.

I have much to be thankful for today.

I hope I continue to live a full life and that the door doesn’t open for me any time soon.

Please not any time soon.

I don't want my picture on the news rack, my obit posted on some bulletin board, people thinking, yeah, I knew that guy. We did a few calls together. I used to see him around.

When I get to the base, I can see from the tracks in the snow by the ambulance doors. The night crew is out on a call. Ten minutes later I hear them clear with a presumption. I sit in the office and drink a diet coke while I read the morning paper.

This week a thirty-year-old female cop in one of the suburban towns was murdered by her ex-boyfriend, a state cop. We had two cars on standby while they looked for the shooter. They found him a couple hours later, also dead. The paper said he parked his car at a park, and then walked over to her house so she wouldn’t see him. He lay in wait for her and when she returned from work, he ambushed her, shooting her three times, twice in the chest and once in the head. He was supposed to turn himself into court today on a police charge, but instead he called his lawyer and said there was a change in plans. The lawyer got the message a couple hours later and alerted police. Her new boyfriend -- another cop -- came home and found her.

I knew her by face, not by name. I’d been on calls with her a few times over the six years. I remember when she first started working. She was gorgeous. It was hard to believe someone that good-looking would chose to be a cop. Lately I noticed she’d started to wear a bit more makeup around her eyes, her face seemed a little heavier. She never had much to say to us, at least on the calls I went on. She was all business. If she pulled you over, I don't think you'd want to sweet talk her. I’m sure she had a warm side she showed to those who knew her.

The paper in the news rack the next day had a headline “A Cop’s Fury.” It had pictures of the two dead on the front. It made me think, you are here one day, and the next people are walking by the news rack with your picture on it, only you aren’t one of the people walking by to see it.

**

We did a call in her town this morning, and said our condolences to the two cops who were there. They had black bands over their badges. The call was for an old woman who said she had taken a handful of painkillers. She said she did it because she was stupid. She said her ex-husband and her doctor would be mad. I got the feeling from the cops they were at this house all the time for similar vague complaints of taking too many pills. “I don’t need this today,” one cop said to me.

**

All week I have found myself in idle moments thinking about the dead policewoman. I guess she probably never figured her death was coming that day. She comes home from work, sits down with computer and then suddenly there is the angry man in her house, gun drawn coming at it. Did she know she was going to die?

When do heart attack victims get that sense that right now what is happening -- this sudden pain in their chest -- might be their end? And car crash victims – they start to loose control and see the tree or the truck careening toward them?

Last New Year’s Eve another cop in the same department was gunned down at a domestic. I knew him too, but also just in passing. We’d been on calls together. A nice, big friendly man. He walked down the basement stairs and then shooter pulled the trigger on a machine gun. Did he have time to realize his end had come?

This summer a paramedic student who rode with me was on a jet ski with his girl friend in Florida when they were blindsided by a boat. I heard about it when I saw his obituary posted at the office. Did he hear the roar of the engine? Did he turn to see it bearing down on him? What did he think in those moments?

Last Saturday they held a memorial for a flight nurse who died in a helicopter crash 13 years ago. I was working in the health department at the time and remember the late night call I got telling me about the crash. I’d seen her around the ER a few times when I brought in patients as a volunteer EMT. And I had ridden in the helicopter as a third rider only a month before. The accident happened when the copter clipped a wire while trying to land near a highway rest stop, a rest stop that now bears her name. When the copter started spinning, did she know?

I don’t mean to be morbid.

The saddest thing about all these deaths is not just the fear they must have felt when they saw what was happening to them, but that fact that everything that would have happened in their lives and all the people they would have affected is just gone. The children the might have had, the things those children would have gone on to do, the memories – all of it vanished. That’s the tragedy.

Death happens everyday and we see it in this job, but it doesn’t impact as much unless it is one of us. You can grow immune to it until it comes close like it has again this week.

But I don’t worry as much about dying as I used to. I’ve lived awhile now and feel lucky to have made it as long as I have. If the deal was when I was born, I agreed to come out of the womb, but in return I would only have these 47 years, I'd take that deal anytime.

I have many, many years ahead I hope. But if I were to die today, if the door were to open and death were to be there, I would be terrified, but I can’t say that I would have been cheated. Life, with its share of sadness and disappointments, has been largely good to me. And today I am as excited about life and its possibilities as I ever have been, excited not in the wild way I was as a youth, but in the more realistic sense that I can enjoy the moments now and not just the thought of the goal.

I want to live fully and feel, for the most part, I have been. I work a lot, but I like my job and the money I make will help me keep doing what I love – being a paramedic, writing, going to foreign countries to help the poor, getting good seats to a Red Sox game every year, living in my house which I feel comfortable in, being able to eat a good steak, and drink a cold beer when I want without having to count nickels on the liquor store counter.

I have much to be thankful for today.

I hope I continue to live a full life and that the door doesn’t open for me any time soon.

Please not any time soon.

I don't want my picture on the news rack, my obit posted on some bulletin board, people thinking, yeah, I knew that guy. We did a few calls together. I used to see him around.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Anonymous-"I'm Human"

The following comment was posted on one of my entries by "anonymous." I thought it was so good, I am reposting it here so those who don't normally read the comments can read it. So to "anonymous" I hope you don't mind my reposting this here. Thank you for your moving account.

Anonymous said...

I struggle with the issues of spirituality. I went on a messy car accident call the other day where some people had been tossed from car that rolled off the road. They were teenagers. One of them was dead right there. Four of the others were transported, and one died a few days later in the hospital.

All five of the occupants, I found out in the newspaper, were close friends. Two were twin brothers. One twin died, the other was the one who died in the hospital. In the space of a week, a mother lost two of her sons.

I live two blocks from where one of the dead twins lived. The church down the street held a prayer vigil for the twin that'd been in the hospital.

Normally, it's pretty anonymous. But this wasn't anonymous enough. I didn't know these people personally, and when I saw the obits, I didn't recognize their picture. In the obit pic, they didn't have blood on their face and vomit in their hair. They didn't have a ET tube in them, or a BVM by their face. They didn't have blood coming out of their ears, or a bone sticking out of their leg. Everyone else remembers them as they lived. I remember them as they died.

I heard people talk about how it was part of God's plan, and how there will be something good that comes out of it.

But to me, it's just shitty luck. They might have been drinking, but no matter what the state police say, it's possible the alcohol wasn't THE factor. Maybe it was changing the radio station at the wrong time, or a tire blowout, or a cell phone call at exactly the wrong time.

I don't know what kind of Plan requires one brother to die in a ditch, and the other to aspirate his stomach contents and die on the vent in the ICU.

I don't see the Good that comes out of something like that. It's shitty luck, that's all. No plan, nothing fantastic. Just another grieving family. All the prayer in the world from all the caring people and pastors didn't help those boys live. They died, but their memories live on in those who didn't. That's the afterlife as I see it.

That call really bothered me for a while. It was one of the first really bad trauma calls I've seen. I'm new, that's why. And that's why it really bothered me.

For two or three days, I kept seeing the mangled bodies around the car. I kept seeing the bloody ambulance floor.

I never once had that whole 'If only I'd..." thing. I know that what we did was flawless. Nothing could save that person. The best I could do was to do my job well enought to, maybe, make it possible for them to die with their family nearby in the hospital.

I'll never forget that call, ever. That moment changed the lives of a lot of people forever. It changed mine too. I learned more about myself and this work and this world in that instant than I ever remember learning before.

In a way, that boy that died lives on in me. He's in my memories. I wish I could say it didn't bother me, but hey, I'm human.

I mention this because your post made me think about the amazing privledge people in EMS have in seeing such unadulerated emotions -- love and hate and terror and joy and fear and relief in such pure forms.

There's precious few times when one can see this in the world, these pure expressions of the human experience.

It is, I think, the best part of EMS -- the honor of being present at so many life changing events. It's not often spoken of in EMS: the honor of bearing witness and filling in the collective memory.

10:41 PM

Anonymous said...

I struggle with the issues of spirituality. I went on a messy car accident call the other day where some people had been tossed from car that rolled off the road. They were teenagers. One of them was dead right there. Four of the others were transported, and one died a few days later in the hospital.

All five of the occupants, I found out in the newspaper, were close friends. Two were twin brothers. One twin died, the other was the one who died in the hospital. In the space of a week, a mother lost two of her sons.

I live two blocks from where one of the dead twins lived. The church down the street held a prayer vigil for the twin that'd been in the hospital.

Normally, it's pretty anonymous. But this wasn't anonymous enough. I didn't know these people personally, and when I saw the obits, I didn't recognize their picture. In the obit pic, they didn't have blood on their face and vomit in their hair. They didn't have a ET tube in them, or a BVM by their face. They didn't have blood coming out of their ears, or a bone sticking out of their leg. Everyone else remembers them as they lived. I remember them as they died.

I heard people talk about how it was part of God's plan, and how there will be something good that comes out of it.

But to me, it's just shitty luck. They might have been drinking, but no matter what the state police say, it's possible the alcohol wasn't THE factor. Maybe it was changing the radio station at the wrong time, or a tire blowout, or a cell phone call at exactly the wrong time.

I don't know what kind of Plan requires one brother to die in a ditch, and the other to aspirate his stomach contents and die on the vent in the ICU.

I don't see the Good that comes out of something like that. It's shitty luck, that's all. No plan, nothing fantastic. Just another grieving family. All the prayer in the world from all the caring people and pastors didn't help those boys live. They died, but their memories live on in those who didn't. That's the afterlife as I see it.

That call really bothered me for a while. It was one of the first really bad trauma calls I've seen. I'm new, that's why. And that's why it really bothered me.

For two or three days, I kept seeing the mangled bodies around the car. I kept seeing the bloody ambulance floor.

I never once had that whole 'If only I'd..." thing. I know that what we did was flawless. Nothing could save that person. The best I could do was to do my job well enought to, maybe, make it possible for them to die with their family nearby in the hospital.

I'll never forget that call, ever. That moment changed the lives of a lot of people forever. It changed mine too. I learned more about myself and this work and this world in that instant than I ever remember learning before.

In a way, that boy that died lives on in me. He's in my memories. I wish I could say it didn't bother me, but hey, I'm human.

I mention this because your post made me think about the amazing privledge people in EMS have in seeing such unadulerated emotions -- love and hate and terror and joy and fear and relief in such pure forms.

There's precious few times when one can see this in the world, these pure expressions of the human experience.

It is, I think, the best part of EMS -- the honor of being present at so many life changing events. It's not often spoken of in EMS: the honor of bearing witness and filling in the collective memory.

10:41 PM

Friday, November 18, 2005

Airway

Did a code at a nursing home last week. Patient, last seen allegedly an hour earlier, found apneic and pulseless in bed. She was asystole with cool, cyanotic skin. No shock advised on the first responders' defibrillator. I intubated her, did a round of epi down the tube, then got an IV and did 25 minutes of ACLS, including 25 grams of Dextrose because her sugar was less than 20, but got nothing back, and so I presumed her. It wasn't until I came back to the base and was writing up the presumption that I recognized the medical history as someone who I had transported a few days earlier for a broken knee. Dead people really have nothing in their faces because I had not a clue that I had actually been talking to this person so recently.

When I did the tube, I didn't initially see the chords, but with my right hand, I applied crick pressure for myself, using my fingers like the fingers on a flute to find the right spot -- a modification of a technique I learned in a half-day airway class at the JEMS conference in Phillidelphia three years ago. The idea is that the intubator has much better control of the manipulation than a third party. When I pressed down with my middle finger tip the chords dropped right down into view. I said to my partner. "See where I am pressing with my finger. Put your fingertip right there." She put it right in the right spot, and I easily slipped the tube in. The technique doesn't always work so well, but it has helped me out a number of times.

The half-day airway class I took in Philidelphia was taught by Richard M. Levitan, M.D. He is the guy behind the airway cam videos and book. It was a great course. I went to his web site recently and see he offers a two day class with everyone getting their own cadaver for the second day. It's pricey, but I'm thinking about doing it at some point. Anything to help improve my airway skills.

Practical Emergency Airway management Course

Airway Cam Home

Airway Tips

The Airway Cam Guide to Intubation and Practical Emergency Airway Management

A couple years ago, I also took a two day class taught locally called D.A.M.S. (Difficult Airway Management in the Streets) that was also excellent. That was taught by Daniel and David Tauber. The class culminated in an airway tunnel where we had to crawl under tables in a dark room illuminated only by light sticks from one airway station to the next -- each station (there were 10 of them) involved a different airway scenario (basic ET, nasal, broken equipment, pedi, combitube, awkward positining requiring "icepick" technique, etc.)

I have also heard of an airway class called SLAM(Street Level Airway Management) that I would love to take someday.

SLAM

You can never know too much about the airway.

When I did the tube, I didn't initially see the chords, but with my right hand, I applied crick pressure for myself, using my fingers like the fingers on a flute to find the right spot -- a modification of a technique I learned in a half-day airway class at the JEMS conference in Phillidelphia three years ago. The idea is that the intubator has much better control of the manipulation than a third party. When I pressed down with my middle finger tip the chords dropped right down into view. I said to my partner. "See where I am pressing with my finger. Put your fingertip right there." She put it right in the right spot, and I easily slipped the tube in. The technique doesn't always work so well, but it has helped me out a number of times.

The half-day airway class I took in Philidelphia was taught by Richard M. Levitan, M.D. He is the guy behind the airway cam videos and book. It was a great course. I went to his web site recently and see he offers a two day class with everyone getting their own cadaver for the second day. It's pricey, but I'm thinking about doing it at some point. Anything to help improve my airway skills.

Practical Emergency Airway management Course

Airway Cam Home

Airway Tips

The Airway Cam Guide to Intubation and Practical Emergency Airway Management

A couple years ago, I also took a two day class taught locally called D.A.M.S. (Difficult Airway Management in the Streets) that was also excellent. That was taught by Daniel and David Tauber. The class culminated in an airway tunnel where we had to crawl under tables in a dark room illuminated only by light sticks from one airway station to the next -- each station (there were 10 of them) involved a different airway scenario (basic ET, nasal, broken equipment, pedi, combitube, awkward positining requiring "icepick" technique, etc.)

I have also heard of an airway class called SLAM(Street Level Airway Management) that I would love to take someday.

SLAM

You can never know too much about the airway.

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Nursing Home Artwork

I’m wheeling a patient down the hall in nursing home (bringing them back from a dialysis trip), looking at the paintings on the wall. Most nursing homes have really crappy art work -- paintings of rich people having picnics in top hats or girls in nightgowns playing with kittens -- paintings that are sold in crappy five and dime stores for $15 each -- really bland paintings that are supposed to I guess in some way provide comfort and peace and thus cause patients to fall asleep with their mouths open because the paintings are so lifeless and boring. That would be my idea of hell, ending up having to spend my last years looking at those paintings. Please let me out of here!

But this nursing home has a Van Gogh – Irises.

A nice painting.

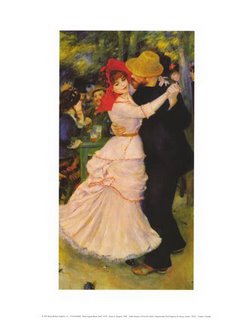

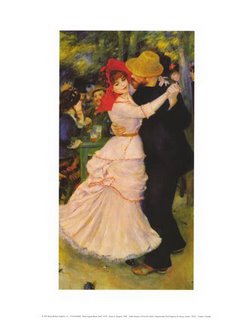

I could handle a nursing home with a good collection of impressionist prints. I think if I could have any one painting I would want Renoir's Dance at Bougival.

I could stare at that painting and remember what it was like to hold a woman in my arms.

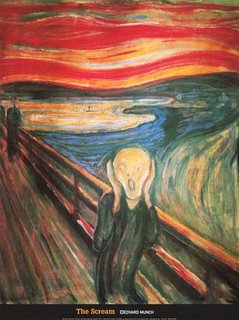

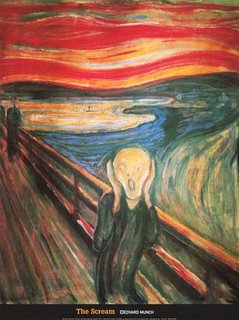

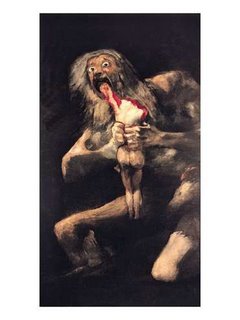

Though I suppose when I am in a nursing home I may be a little demented, and want something that mirrors my inner thoughts. I could ask for a print of Munch’s The Scream:

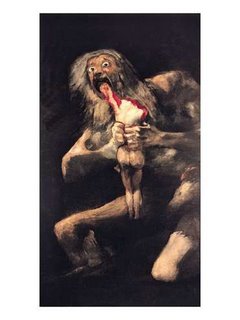

Or some Goya. "Satan Devouring one of His Own Children."

But the administrators probably wouldn't let me hang those up. Can't scare away families looking to place their loved ones.

But this nursing home has a Van Gogh – Irises.

A nice painting.

I could handle a nursing home with a good collection of impressionist prints. I think if I could have any one painting I would want Renoir's Dance at Bougival.

I could stare at that painting and remember what it was like to hold a woman in my arms.

Though I suppose when I am in a nursing home I may be a little demented, and want something that mirrors my inner thoughts. I could ask for a print of Munch’s The Scream:

Or some Goya. "Satan Devouring one of His Own Children."

But the administrators probably wouldn't let me hang those up. Can't scare away families looking to place their loved ones.

Sunday, November 13, 2005

EMS Errors/Dangerous Places

Interesting online article at Slate.com about ambulance errors.

Ambulances Can Be Dangerous Places

Here's two excerpts:

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published its report To Err Is Human, which estimated that up to 98,000 patients may die each year because of the mistakes of doctors, nurses, and other hospital workers. But few published studies have tried to quantify or even characterize the injuries to patients that take place before they reach the hospital. How frequent and how serious are the mistakes that take place in ambulances—and are there simple changes that could help prevent them?

Based on what we know about hospital-based medical error, ambulances may be one of the more dangerous places to be a patient. Studies have shown that medical error is more common when conditions are variable, like in the emergency room, than it is in other parts of the hospital. The problem likely has little to do with experience or skill. Instead it's about the lack of predictability: Doctors and nurses make more mistakes when they work under changing conditions. Think about that and compare the working conditions of paramedics and EMTs with an operating room. Before surgery, an entire staff is prepped with information about a patient's condition, medical history, and the anticipated plan of action. On an ambulance run, there is no plan. Paramedics and EMTs have to improvise as they encounter the obese, frail, terrified, combative, near-dead, stoned, violent, and newly born. And they have to deliver care in a cramped space with relatively few resources.

***

Thought-provoking article, although I would have to disagree with its assumption that ambulances are more dangerous than hospitals. I think in EMS, we have less ways to make errors. In many ways, while our scenes are all varied, the situations are often common -- MI, Stroke, CHF, asthma, hypoglycemia, etc -- and since we have general protocols we follow, the medical care is often routine to us (by routine I don't mean cookbook), even under the most trying circumstances. Difficult situations are after all our norm. Another critical point in our favor is that we are the ones deciding on and providing the care. There are no misunderstandings when one person is both drawing up the drug and delievering it.

***

At my monthly EMS meetings we often talk about the problems of quality assurance. As the number of patient runs increases, and as people charged with QA, whether ambulance service employees or hospital clinical care coordinators have increasing demands on their time, QA inevitably suffers. I recently heard the laments of a fellow paramedic who works for another service complain that his service posted spread sheets detailing employee compliance with filling out billing information -- everything from getting the patient's signature to their next of kin's name -- but nothing has been done to QA the front of the form or discover compliance with taking regular vital signs, giving ASA for chest pain, etc.

***

If there are major errors in EMS, they are most likely system errors. If you were to ask me what is the most dangerous part of being in an ambulance, I would say it is traveling in an ambulance lights and sirens.

Check out this site to view daily ambulance crash logs:

Ambulance Crash Log

Check out these articles from the Detroit News:

Unsafe Saviours

From USA Today:

Speeding to the rescue Can Have Deadly Results

***

For our regional council medical advisory committee, I have been researching lights and sirens protocols to the hospital. Some very interesting items.

1. The National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians (NAEMSP) Position Paper on the issue. Use of Warning Lights and Siren in Emergency Medical Vehicle Response and Patient Transport

2. A Merginet Article: Curtailing Emergency Driving Saves Money and Lives

3. A Pennsylvania Regional Council's Newletter Discussing Issue and the new PA regs.Lights and Sirens Use: It is a Big deal to EMS Services!

4: A PA Service's Policy/ Foxwell EMS: (PA): Emergency Response Policy

5. A disccusion group arguing merits/drawbacks of transport AMI patient's lights and sirens. Lights and Sirens Transport of AMI Patients

***

People are just used to lights and sirens being a part of the EMS system even when they are largely unneccessary. This part week they sent us lights and sirens for the 12 year old violent psych, police on scene. The next was also lights and sirens for the 9 year old misbehaving on one of the floors at a pyschiatric hospital. What is wrong with these pictures? Cops on scene and a patient in a psychiatric hospital and they need an ambulance lights and sirens to save the day? In both cases as expected the scenes were well under control before we arrived.

One of the protocols listed above recommends that lights and sirens not be used for cardiac arrests except in cases of trauma, persistent vfib, hypothermia, or drug overdose. I did a code a week ago -- an old woman found face down against the steering wheel of her car outside a doctor's office. She was cold, but still limber. Asystole on the monitor. We worked for a little bit, then since we were already in the ambulance started to the hospital. I told my crew I wanted to go on a priority 2. They revolted. They called me all sorts of names and insisted on going lights and sirens. They said I was crazy. But the lady was dead. Driving fast in fact made CPR harder to do effectively. I am hoping for a sea change in the way we use lights and sirens.

Until there is that sea change, ambulances will continue to be dangerous places.

Ambulances Can Be Dangerous Places

Here's two excerpts:

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published its report To Err Is Human, which estimated that up to 98,000 patients may die each year because of the mistakes of doctors, nurses, and other hospital workers. But few published studies have tried to quantify or even characterize the injuries to patients that take place before they reach the hospital. How frequent and how serious are the mistakes that take place in ambulances—and are there simple changes that could help prevent them?

Based on what we know about hospital-based medical error, ambulances may be one of the more dangerous places to be a patient. Studies have shown that medical error is more common when conditions are variable, like in the emergency room, than it is in other parts of the hospital. The problem likely has little to do with experience or skill. Instead it's about the lack of predictability: Doctors and nurses make more mistakes when they work under changing conditions. Think about that and compare the working conditions of paramedics and EMTs with an operating room. Before surgery, an entire staff is prepped with information about a patient's condition, medical history, and the anticipated plan of action. On an ambulance run, there is no plan. Paramedics and EMTs have to improvise as they encounter the obese, frail, terrified, combative, near-dead, stoned, violent, and newly born. And they have to deliver care in a cramped space with relatively few resources.

***

Thought-provoking article, although I would have to disagree with its assumption that ambulances are more dangerous than hospitals. I think in EMS, we have less ways to make errors. In many ways, while our scenes are all varied, the situations are often common -- MI, Stroke, CHF, asthma, hypoglycemia, etc -- and since we have general protocols we follow, the medical care is often routine to us (by routine I don't mean cookbook), even under the most trying circumstances. Difficult situations are after all our norm. Another critical point in our favor is that we are the ones deciding on and providing the care. There are no misunderstandings when one person is both drawing up the drug and delievering it.

***

At my monthly EMS meetings we often talk about the problems of quality assurance. As the number of patient runs increases, and as people charged with QA, whether ambulance service employees or hospital clinical care coordinators have increasing demands on their time, QA inevitably suffers. I recently heard the laments of a fellow paramedic who works for another service complain that his service posted spread sheets detailing employee compliance with filling out billing information -- everything from getting the patient's signature to their next of kin's name -- but nothing has been done to QA the front of the form or discover compliance with taking regular vital signs, giving ASA for chest pain, etc.

***

If there are major errors in EMS, they are most likely system errors. If you were to ask me what is the most dangerous part of being in an ambulance, I would say it is traveling in an ambulance lights and sirens.

Check out this site to view daily ambulance crash logs:

Ambulance Crash Log

Check out these articles from the Detroit News:

Unsafe Saviours

From USA Today:

Speeding to the rescue Can Have Deadly Results

***

For our regional council medical advisory committee, I have been researching lights and sirens protocols to the hospital. Some very interesting items.

1. The National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians (NAEMSP) Position Paper on the issue. Use of Warning Lights and Siren in Emergency Medical Vehicle Response and Patient Transport

2. A Merginet Article: Curtailing Emergency Driving Saves Money and Lives

3. A Pennsylvania Regional Council's Newletter Discussing Issue and the new PA regs.Lights and Sirens Use: It is a Big deal to EMS Services!

4: A PA Service's Policy/ Foxwell EMS: (PA): Emergency Response Policy

5. A disccusion group arguing merits/drawbacks of transport AMI patient's lights and sirens. Lights and Sirens Transport of AMI Patients

***

People are just used to lights and sirens being a part of the EMS system even when they are largely unneccessary. This part week they sent us lights and sirens for the 12 year old violent psych, police on scene. The next was also lights and sirens for the 9 year old misbehaving on one of the floors at a pyschiatric hospital. What is wrong with these pictures? Cops on scene and a patient in a psychiatric hospital and they need an ambulance lights and sirens to save the day? In both cases as expected the scenes were well under control before we arrived.

One of the protocols listed above recommends that lights and sirens not be used for cardiac arrests except in cases of trauma, persistent vfib, hypothermia, or drug overdose. I did a code a week ago -- an old woman found face down against the steering wheel of her car outside a doctor's office. She was cold, but still limber. Asystole on the monitor. We worked for a little bit, then since we were already in the ambulance started to the hospital. I told my crew I wanted to go on a priority 2. They revolted. They called me all sorts of names and insisted on going lights and sirens. They said I was crazy. But the lady was dead. Driving fast in fact made CPR harder to do effectively. I am hoping for a sea change in the way we use lights and sirens.

Until there is that sea change, ambulances will continue to be dangerous places.

Friday, November 11, 2005

Scouting Report

The local EMT class lets its students sign up to ride with us after they have made it through a certain part of the course. Over the years I have to say most of the students who ride with us don't last. The course has a poor passing rate, and many of the students who do pass rarely enter the field. Every now and then, you get a student that you can glimpse real potential in. There is a young man in the current class I feel this way about.

He comes from a lower middle class family, and was a football player on the state high school championship team a few years ago. He observed with us for the first time last week when we did two calls during the hours he rode. He did well with the blood pressures. If he couldn't hear it, he didn't lie about it. I helped him reposition his stethescope, then he got it properly. We let him pull the stretcher out with the patient on it, and even work the radio with the local CMED. When I explained to him what I was doing, his eyes were fixed on me. I also like that on his own, he made an effort to see that the patient was comfortable, positioning a pillow or pulling up a blanket.

Today was his second time riding. On the first call, he made conversation with the elderly gentleman who had a possible urinary blockage, took his blood pressure and with coaching, gave the radio report to the hospital.

Our second call was for a woman with back pain. She had a history of bulging disks and when she bent down in her office, then straightened up, she did something to her back that was causing her extreme pain. She was in tears when we got there. We tried to get her to sit on the stretcher, but she couldn't manage -- the pain of moving was too great. I called and got orders for morphine. I pushed it slowly, and the woman found the rush very uncomfortable. I stopped at 2 milligrams -- not enough to make a dent in her pain -- she weighed 260. Since we still couldn't get her on the stretcher, I convinced her to let me give her more morphine. I promised to go a little at a time, and very slowly.

The student held her hand while I pushed the medicine through the IV lock. She squeezed his hand tightly. The woman, while in obvious pain, had a great deal of anxiety as well as low tolerance for any procedure -- be it the IV or taking her blood pressure again to make certain her pressure was maintaining. Through it all, the young man, tried to reassure her.

While I was pushing the fifth and sixth milligram -- still unable to get the pain down enough to get her to swing her legs up onto the stretcher, I noticed the young man start to lean. Like a big tree, he slowly teetered, as his eyes rolled back into his head. Then he slumped to the ground. Out cold.

"It's okay," I reassured the patient and the onlookers -- two of her fellow employees. "He just fainted. He'll be okay."

While my partner attended him, I finished giving the woman the morphine.

The young man was helped to a chair, where he hung his head.

"Don't worry," I said, "happens to the best of us."

My partner helped him off with his jacket and outer shirt, then before I knew it, he had resumed his place holding the woman's hand.

"Are you okay?" she asked.

"Yeah," he said. "I just got a little hot. Are you feeling any better?"

"A little," she said, "Thank you."

After ten of morphine and nearly an hour on scene, we finally were on our way to the hospital. The woman, now pain-free, put her hand in his hand. They talked on the way in. At the hospital, he again helped make her comfortable. When he said goodbye, he shook her hand and she wished him well, calling him by his first name.

"Nice job," I said to him as we walked back to the ambulance.

When we got back to the station after the call, he signed up for another shift next week.

I tell you, he can play on my team anytime.

Scouting Report: The kid can take a hit.

He comes from a lower middle class family, and was a football player on the state high school championship team a few years ago. He observed with us for the first time last week when we did two calls during the hours he rode. He did well with the blood pressures. If he couldn't hear it, he didn't lie about it. I helped him reposition his stethescope, then he got it properly. We let him pull the stretcher out with the patient on it, and even work the radio with the local CMED. When I explained to him what I was doing, his eyes were fixed on me. I also like that on his own, he made an effort to see that the patient was comfortable, positioning a pillow or pulling up a blanket.

Today was his second time riding. On the first call, he made conversation with the elderly gentleman who had a possible urinary blockage, took his blood pressure and with coaching, gave the radio report to the hospital.

Our second call was for a woman with back pain. She had a history of bulging disks and when she bent down in her office, then straightened up, she did something to her back that was causing her extreme pain. She was in tears when we got there. We tried to get her to sit on the stretcher, but she couldn't manage -- the pain of moving was too great. I called and got orders for morphine. I pushed it slowly, and the woman found the rush very uncomfortable. I stopped at 2 milligrams -- not enough to make a dent in her pain -- she weighed 260. Since we still couldn't get her on the stretcher, I convinced her to let me give her more morphine. I promised to go a little at a time, and very slowly.

The student held her hand while I pushed the medicine through the IV lock. She squeezed his hand tightly. The woman, while in obvious pain, had a great deal of anxiety as well as low tolerance for any procedure -- be it the IV or taking her blood pressure again to make certain her pressure was maintaining. Through it all, the young man, tried to reassure her.

While I was pushing the fifth and sixth milligram -- still unable to get the pain down enough to get her to swing her legs up onto the stretcher, I noticed the young man start to lean. Like a big tree, he slowly teetered, as his eyes rolled back into his head. Then he slumped to the ground. Out cold.

"It's okay," I reassured the patient and the onlookers -- two of her fellow employees. "He just fainted. He'll be okay."

While my partner attended him, I finished giving the woman the morphine.

The young man was helped to a chair, where he hung his head.

"Don't worry," I said, "happens to the best of us."

My partner helped him off with his jacket and outer shirt, then before I knew it, he had resumed his place holding the woman's hand.

"Are you okay?" she asked.

"Yeah," he said. "I just got a little hot. Are you feeling any better?"

"A little," she said, "Thank you."

After ten of morphine and nearly an hour on scene, we finally were on our way to the hospital. The woman, now pain-free, put her hand in his hand. They talked on the way in. At the hospital, he again helped make her comfortable. When he said goodbye, he shook her hand and she wished him well, calling him by his first name.

"Nice job," I said to him as we walked back to the ambulance.

When we got back to the station after the call, he signed up for another shift next week.

I tell you, he can play on my team anytime.

Scouting Report: The kid can take a hit.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

"You're Going to Need a Bigger Ambulance"

"You're going to need a bigger ambulance," the police officer says when we pull up in our van.

"I don't like the sound of that," my partner says.

Niether do I. Already I can feel my back tightening up.

Inside the small dirty apartment we find a tiny older woman, who points us down a hallway. At the end of the hallway in the bedroom, our patient sits on the edge of his large bed, leaning against a cane. I'm guessing he is 600 pounds -- a wide 600 pounds. The man, in his late thirties, says this is the heaviest he has felt, and his heaviest recorded weight is 619. He says he has been retaining water and feels bloated. "I can't even get up to go to the bathroom anymore," he says. "I had to pee into a water pitcher just now," he says. "Basically I'm drowning in my own fat."

I pride myself on my ability to figure out situations, but when we find out that our bariatric ambulance, which is capable of transporting people up to 1000 pounds is out on a distant call, I am at a loss. Our dispatcher tells us to unscrew our stretcher mount and use a fire department stokes basket. The problem is the local department's basket is only rated for 350 pounds, plus the man cannot lay flat. He is too heavy and too wide to even consider our stretcher. And there is no way he could walk out to the ambulance and try to step in and sit.

While we are trying to figure out what to do, the tiny woman, who by now we know is the patient's mother, asks her son if it is okay if she has a can on his minestone soup. He thinks about it, then says, "okay, I guess, go ahead, you eat it."

Strange.

Back to what to do with him. The only option I see is to get a flatbed truck, but it is pouring rain out. The cop finally comes up with the solution. He looks stable, why don't you just wait for the big ambulance. They tell us it will be an hour and a half at least. But the man's problem is not acute. The bottom line is he's 600 plus pounds and feels crappy because of it. He agrees to wait for the big ambulance, signs a refusal, and says he will call us back if he experiences any problems while waiting.

We go back out to the ambulance and clear. Our dispatcher won't let us leave the scene. He sends a supervisor on a priority to see what is going on. They had sent us on a priority one for difficulty breathing, we have mentioned the patient is large, and now we are clearing refusal. Sounds suspicious, even though we have thoroughly assessed the patient and found him stable and we did set it up with one of the dispatchers to have the big ambulance sent to the address as soon as it is available. We meet the supervisor outside, and explain the situation. This is a chronic problem, not an acute problem. Since we have a bariatric ambulance, and there is no rush, it makes the most sense to wait till it is available, as opposed to taking him in through the rain on the back of a flatbed. He won't fit in one of our van ambulances. The patient prefers to wait for the big ambulance. We go back in to talk to the patient. We find him happily eating cherry popsicles.

***

They station us near the scene. We are certain that when the big ambulance becomes available, we will be sent to do the call. Then we get called for another emergency in the town. While we are on scene, we hear a crew being dispatched for the 600 plus pound man. We hear later that when the crew of the bariatric ambulance takes him in, the hospital staff says, don't leave, he'll be going home as soon as the doctor sees him. Evidently, he is a frequent flyer, although an increasingly larger frequent flyer.

The call we are at is for a man with COPD and a probable respiratory infection. I have taken him in before. He is the man who called the ambulance a few moments before the child was run over by his mother in the same town. If he hadn't called 911 when he did, my partner and I would have been the crew dispatched to that horrific scene. He spared us from that call, and now he has spared us from the 600 pound transport. I shake his hand when I say good bye to him at the hospital.

"I don't like the sound of that," my partner says.

Niether do I. Already I can feel my back tightening up.

Inside the small dirty apartment we find a tiny older woman, who points us down a hallway. At the end of the hallway in the bedroom, our patient sits on the edge of his large bed, leaning against a cane. I'm guessing he is 600 pounds -- a wide 600 pounds. The man, in his late thirties, says this is the heaviest he has felt, and his heaviest recorded weight is 619. He says he has been retaining water and feels bloated. "I can't even get up to go to the bathroom anymore," he says. "I had to pee into a water pitcher just now," he says. "Basically I'm drowning in my own fat."

I pride myself on my ability to figure out situations, but when we find out that our bariatric ambulance, which is capable of transporting people up to 1000 pounds is out on a distant call, I am at a loss. Our dispatcher tells us to unscrew our stretcher mount and use a fire department stokes basket. The problem is the local department's basket is only rated for 350 pounds, plus the man cannot lay flat. He is too heavy and too wide to even consider our stretcher. And there is no way he could walk out to the ambulance and try to step in and sit.

While we are trying to figure out what to do, the tiny woman, who by now we know is the patient's mother, asks her son if it is okay if she has a can on his minestone soup. He thinks about it, then says, "okay, I guess, go ahead, you eat it."

Strange.

Back to what to do with him. The only option I see is to get a flatbed truck, but it is pouring rain out. The cop finally comes up with the solution. He looks stable, why don't you just wait for the big ambulance. They tell us it will be an hour and a half at least. But the man's problem is not acute. The bottom line is he's 600 plus pounds and feels crappy because of it. He agrees to wait for the big ambulance, signs a refusal, and says he will call us back if he experiences any problems while waiting.

We go back out to the ambulance and clear. Our dispatcher won't let us leave the scene. He sends a supervisor on a priority to see what is going on. They had sent us on a priority one for difficulty breathing, we have mentioned the patient is large, and now we are clearing refusal. Sounds suspicious, even though we have thoroughly assessed the patient and found him stable and we did set it up with one of the dispatchers to have the big ambulance sent to the address as soon as it is available. We meet the supervisor outside, and explain the situation. This is a chronic problem, not an acute problem. Since we have a bariatric ambulance, and there is no rush, it makes the most sense to wait till it is available, as opposed to taking him in through the rain on the back of a flatbed. He won't fit in one of our van ambulances. The patient prefers to wait for the big ambulance. We go back in to talk to the patient. We find him happily eating cherry popsicles.

***

They station us near the scene. We are certain that when the big ambulance becomes available, we will be sent to do the call. Then we get called for another emergency in the town. While we are on scene, we hear a crew being dispatched for the 600 plus pound man. We hear later that when the crew of the bariatric ambulance takes him in, the hospital staff says, don't leave, he'll be going home as soon as the doctor sees him. Evidently, he is a frequent flyer, although an increasingly larger frequent flyer.

The call we are at is for a man with COPD and a probable respiratory infection. I have taken him in before. He is the man who called the ambulance a few moments before the child was run over by his mother in the same town. If he hadn't called 911 when he did, my partner and I would have been the crew dispatched to that horrific scene. He spared us from that call, and now he has spared us from the 600 pound transport. I shake his hand when I say good bye to him at the hospital.

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

"For the Unconscious"

Calls run in random, almost crazy patterns that sometimes give you cluster days where you are bombarded with all similar calls. Some days its psychs, other days its carry-downs. (What really sucks is when a carry-down cluster intersects with a humongous patient cluster.) Other days it is asthmas or strokes or MVAs. I once had a cluster month of cardiac arrests where I did 10 in just 12 days of work.

Today was “unconscious” cluster day with a side helping of “cardiac arrest.”

Sign on in the morning and we are sent on a non-priority for a sick person in the north end. While enroute, we are switched to a priority one "for the unconscious" at the train station. Get there and can find no one so we clear no patient. Later we are sent "for the unconscious" also in the north end, possible drug overdose and no one is there. In the afternoon, we are sent "for the unconscious" in the height of rush hour. Arrive to find a man slumped over at a bus stop. He is just drunk.

Earlier we are sent for a “fall possible unconscious” at a chicken restaurant in another town. We find a man lying on the ground writing in pain. He says his knee hurts. He has fallen earlier in the day at a senior center – the man is 90 – he felt okay, then went about his way. While eating chicken, the pain became so unbearable he thought he was going to pass out. His knee looks a little deformed, but then so does his other knee. Only a little pain on palpation. His pressure is 93/60 – he says he usually has low pressure. He says he feels dizzy like he is going to pass out. We take him to the hospital – it is very odd – he looks terrible, but he says the pain in his knee isn’t as bad. The one problem with the call for me is he is hard of hearing and he has the most foul breath – it is so foul – it makes me think there is something wrong with his insides. I have to lean forward to shout at him, but then he answers before I can pull my head away and I get hit with a toxic plume of breath. Very unpleasant. We finally get him in the room at the hospital, and then he starts to puke. He fills up three emesis basins with thick food like emesis.

I am writing up my run form, when I hear on the radio of one of our fly car medics in a suburban town that there was a “cardiac arrest” there. Both fly medics are at the hospital writing their run forms up. I get a page then asking any available car to clear, so my partner and I clear and are sent to the cardiac arrest.

It turns out it isn’t a cardiac arrest, but still an interesting call. A forty year old woman, who has had a cardiac arrest a couple months ago and has an implanted defibrillator was mowing the lawn when the thing went off, knocking her on her back. It went off three more times. She is extremely anxious when we get there and worried she is about to die. It is the first time it has ever gone off. I do what I can to reassure her, as well as giving her some Versed to ease her anxiety and take away some of the pain should the defib go off again. Her kids who were with her when it went off are all bawling and we haveto try to calm them down as well.

Toward the end of the day we are sent "for the unconscious" man in a car. Enroute we get an update from one of the fly car medics that the man is in his car in the garage with the engine running. Then before we can get there we get cancelled. I am guessing the fire department got the man out of the garage and the medic called him dead.

Not two minutes go by before we are sent "for the unconscious" – a woman in a car outside a medical building. We arrive first and a woman directs us to a car where I can see someone sitting in the front seat. “I knocked on the glass,” the woman says, “but she wouldn’t move.” The door is open. The woman in the car is elderly, head slumped forward. She is cool and not breathing, but still limber. I shout to my partner that it is a code, and then I pull her out onto the board and do CPR as we wheel her to the stretcher. One of our supervisors has arrived and then the fly car medic. She is asystole. It is nice having two medics with me. All I have to do is hold out my hand and they hand me the ET tube or drawn up drugs. She has the tiniest chords. I am just barely able to get a 7.0 through them. We transport her to a local hospital, but we don’t get anything back. If she had died at home I would have worked her twenty minutes, then called her, but here the twenty minutes aren’t up until we are reaching the hospital. The doctor in room one calls her dead shortly after hearing our report.

***

One funny or not so funny from the day is when we arrive at the scene of the drunk at the bus stop. We pull in to the bus stop opposite traffic so only my partner can see the patient. I get out the passenger door, grab the blue bag from the side of the ambulance, then go around the back, thinking my partner has gone directly to the patient. As Iwalk around the rear, the back door swings hard right into me, catching me dead on. My partner is pulling out the stretcher and whether it’s him throwing the door open or a fierce gust of wind, the door catches me hard and quite by surprise. I give him a tough time about it. Fortunately at six eight, two-twenty-five, and the fact that I had my arm in front of me holding the strap of the blue bag slung over my shoulder, I avoided being knocked flat onto the pavement. I suppose then my partner would have had to have requested another ambulance "for the unconscious.”

Today was “unconscious” cluster day with a side helping of “cardiac arrest.”

Sign on in the morning and we are sent on a non-priority for a sick person in the north end. While enroute, we are switched to a priority one "for the unconscious" at the train station. Get there and can find no one so we clear no patient. Later we are sent "for the unconscious" also in the north end, possible drug overdose and no one is there. In the afternoon, we are sent "for the unconscious" in the height of rush hour. Arrive to find a man slumped over at a bus stop. He is just drunk.

Earlier we are sent for a “fall possible unconscious” at a chicken restaurant in another town. We find a man lying on the ground writing in pain. He says his knee hurts. He has fallen earlier in the day at a senior center – the man is 90 – he felt okay, then went about his way. While eating chicken, the pain became so unbearable he thought he was going to pass out. His knee looks a little deformed, but then so does his other knee. Only a little pain on palpation. His pressure is 93/60 – he says he usually has low pressure. He says he feels dizzy like he is going to pass out. We take him to the hospital – it is very odd – he looks terrible, but he says the pain in his knee isn’t as bad. The one problem with the call for me is he is hard of hearing and he has the most foul breath – it is so foul – it makes me think there is something wrong with his insides. I have to lean forward to shout at him, but then he answers before I can pull my head away and I get hit with a toxic plume of breath. Very unpleasant. We finally get him in the room at the hospital, and then he starts to puke. He fills up three emesis basins with thick food like emesis.

I am writing up my run form, when I hear on the radio of one of our fly car medics in a suburban town that there was a “cardiac arrest” there. Both fly medics are at the hospital writing their run forms up. I get a page then asking any available car to clear, so my partner and I clear and are sent to the cardiac arrest.

It turns out it isn’t a cardiac arrest, but still an interesting call. A forty year old woman, who has had a cardiac arrest a couple months ago and has an implanted defibrillator was mowing the lawn when the thing went off, knocking her on her back. It went off three more times. She is extremely anxious when we get there and worried she is about to die. It is the first time it has ever gone off. I do what I can to reassure her, as well as giving her some Versed to ease her anxiety and take away some of the pain should the defib go off again. Her kids who were with her when it went off are all bawling and we haveto try to calm them down as well.

Toward the end of the day we are sent "for the unconscious" man in a car. Enroute we get an update from one of the fly car medics that the man is in his car in the garage with the engine running. Then before we can get there we get cancelled. I am guessing the fire department got the man out of the garage and the medic called him dead.

Not two minutes go by before we are sent "for the unconscious" – a woman in a car outside a medical building. We arrive first and a woman directs us to a car where I can see someone sitting in the front seat. “I knocked on the glass,” the woman says, “but she wouldn’t move.” The door is open. The woman in the car is elderly, head slumped forward. She is cool and not breathing, but still limber. I shout to my partner that it is a code, and then I pull her out onto the board and do CPR as we wheel her to the stretcher. One of our supervisors has arrived and then the fly car medic. She is asystole. It is nice having two medics with me. All I have to do is hold out my hand and they hand me the ET tube or drawn up drugs. She has the tiniest chords. I am just barely able to get a 7.0 through them. We transport her to a local hospital, but we don’t get anything back. If she had died at home I would have worked her twenty minutes, then called her, but here the twenty minutes aren’t up until we are reaching the hospital. The doctor in room one calls her dead shortly after hearing our report.

***

One funny or not so funny from the day is when we arrive at the scene of the drunk at the bus stop. We pull in to the bus stop opposite traffic so only my partner can see the patient. I get out the passenger door, grab the blue bag from the side of the ambulance, then go around the back, thinking my partner has gone directly to the patient. As Iwalk around the rear, the back door swings hard right into me, catching me dead on. My partner is pulling out the stretcher and whether it’s him throwing the door open or a fierce gust of wind, the door catches me hard and quite by surprise. I give him a tough time about it. Fortunately at six eight, two-twenty-five, and the fact that I had my arm in front of me holding the strap of the blue bag slung over my shoulder, I avoided being knocked flat onto the pavement. I suppose then my partner would have had to have requested another ambulance "for the unconscious.”

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Cigarettes and Tasers

We get sent to a nursing home for a “violent” patient in the lobby. Cops have been notified. We arrive to find a big muscular man about fifty with no legs in a motorized wheelchair waving his fist at a nurse, who stands back about ten feet, shaking her head at him. There are three police officers in the room

Here’s the deal. He goes outside to smoke. Sometimes he ventures too far in his chair they are worried he is going to get hit by a car in the parking lot. Plus, his guardian doesn’t want him smoking so for his health they have put an electronic guard on his chair so when he approaches the front door it locks so he can’t get out. For him at least it’s about freedom and his cigarettes. Don’t mess with a man with no legs’s cigarettes.

The cops tell him since he threatened the nurse and threatened himself, or at least said his life wasn’t worth living, he has to go to the hospital for evaluation.

“Take me to jail,” he says.

The cops don’t want to take him to jail. They want him to go with us. He has called their bluff.

“I ain’t going,” he says. "I have rights."

“You’re not going to win this argument,” one of the cops says. “There are five of us and one of you.”

“I ain’t going.”

“I’ve got a taser,” the cop says.

I’m about to suggest that I have Ativan and Haldol and maybe the chemical restraint will be a better idea if he is going to try to resist, but I can see the man is staring at the cop’s holster that holds the taser. He is probably picturing the same scene that I am. The cop tasering the guy. His big body becoming rigid as the electricity shoots through him, then collapsing limply. Maybe even causing him to pee his pants.

“All right,” he says, clearly unhappy. “You going to see my chair gets put in my room?”

“We’ll take care of it,” the cop says.

“They’re a bunch of thieves here,” he says.

“We’ll keep it safe.”

“Fucking assholes won’t let me smoke,” he says as we head out to the ambulance.

**

Postscript 11/14/05

I go back to this nursing home a couple weeks later and find the same man sitting in his wheelchair about thirty feet from the main door. He's just sitting there staring at it, watching it open as people come in, then close again. If he moves forward the door will lock. If he stays where he is, at least he can feel some breeze on his face. I am tempted to tell my partner to hold the door open, then get behind the guy and make a run for it. Nursing home break! I feel really sorry for the guy. On my way out, he is still there. I stop at the rest room in the hall, but the door is locked. "You need to get a key at the desk," he says, helpfully.

Here’s the deal. He goes outside to smoke. Sometimes he ventures too far in his chair they are worried he is going to get hit by a car in the parking lot. Plus, his guardian doesn’t want him smoking so for his health they have put an electronic guard on his chair so when he approaches the front door it locks so he can’t get out. For him at least it’s about freedom and his cigarettes. Don’t mess with a man with no legs’s cigarettes.

The cops tell him since he threatened the nurse and threatened himself, or at least said his life wasn’t worth living, he has to go to the hospital for evaluation.

“Take me to jail,” he says.

The cops don’t want to take him to jail. They want him to go with us. He has called their bluff.

“I ain’t going,” he says. "I have rights."

“You’re not going to win this argument,” one of the cops says. “There are five of us and one of you.”

“I ain’t going.”

“I’ve got a taser,” the cop says.

I’m about to suggest that I have Ativan and Haldol and maybe the chemical restraint will be a better idea if he is going to try to resist, but I can see the man is staring at the cop’s holster that holds the taser. He is probably picturing the same scene that I am. The cop tasering the guy. His big body becoming rigid as the electricity shoots through him, then collapsing limply. Maybe even causing him to pee his pants.

“All right,” he says, clearly unhappy. “You going to see my chair gets put in my room?”

“We’ll take care of it,” the cop says.

“They’re a bunch of thieves here,” he says.

“We’ll keep it safe.”

“Fucking assholes won’t let me smoke,” he says as we head out to the ambulance.

**

Postscript 11/14/05

I go back to this nursing home a couple weeks later and find the same man sitting in his wheelchair about thirty feet from the main door. He's just sitting there staring at it, watching it open as people come in, then close again. If he moves forward the door will lock. If he stays where he is, at least he can feel some breeze on his face. I am tempted to tell my partner to hold the door open, then get behind the guy and make a run for it. Nursing home break! I feel really sorry for the guy. On my way out, he is still there. I stop at the rest room in the hall, but the door is locked. "You need to get a key at the desk," he says, helpfully.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)